Why Your Brain Doesn't Care If You Can Actually Control Cancer

The Neuroscience of Power

The day before my surgery was cancelled, I thought I had control. Screening twice a year. Genetic testing. Scheduled surgery. Every box checked.

Then the phone rang: "It's malignant."

Every bit of control I thought I had? Gone.

But here's what the neuroscience research reveals: my brain didn't need me to actually control cancer. It just needed me to believe I could control something.

And that changes everything.

What Your Brain Does Under Uncontrollable Stress

When researchers at the Leibniz Institute for Resilience Research put people in fMRI scanners and subjected them to stressors they couldn't control, something specific happened. Uncontrollable stress triggered activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and bilateral insula—regions that coordinate threat response. But when participants could terminate the stressor, even if identical, vmPFC deactivation was attenuated and stress-responsive regions quieted.

Your brain's threat centers respond not to what's happening to you, but to whether you believe you can do something about it.

Under uncontrollable conditions, greater vmPFC recruitment linked to reduced feelings of helplessness. The participants who activated this region more felt less helpless—even though they still couldn't control the situation.

The control didn't have to be real. The perception was enough.

The Three Types of Control Your Brain Recognizes

When I sent that email asking for oncologist referrals, I wasn't controlling cancer. I was controlling my response. My brain registered that as power.

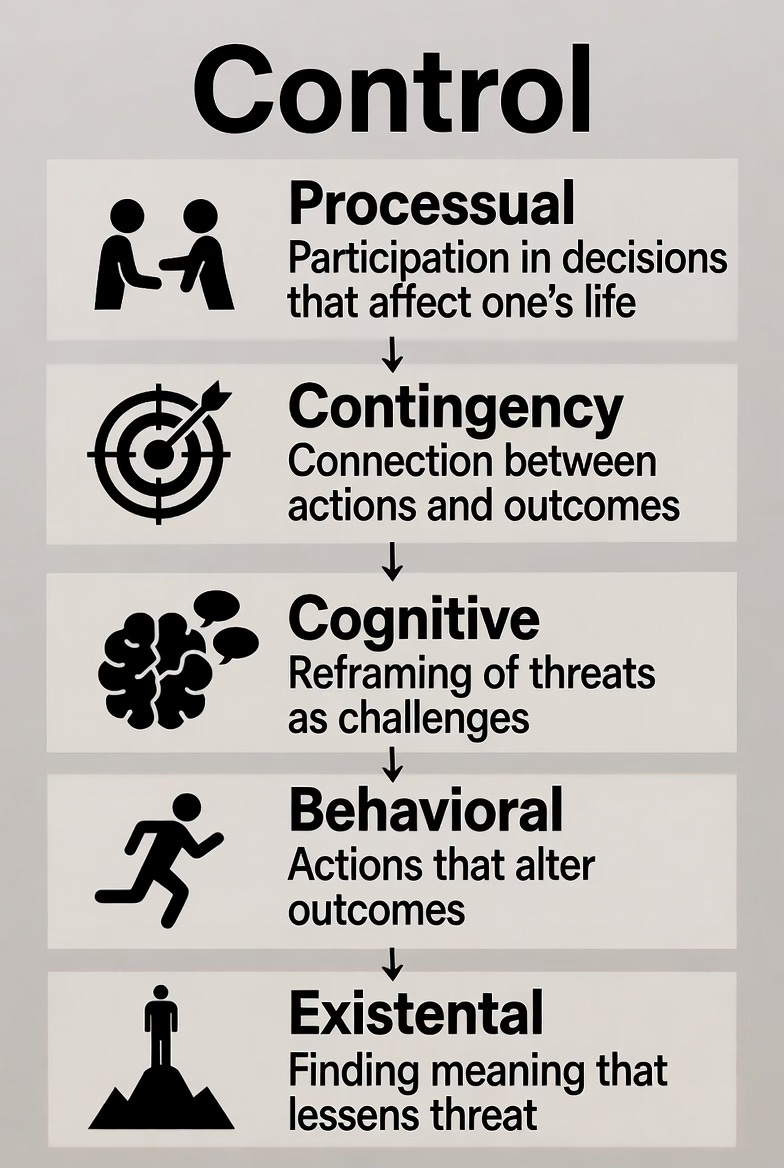

Research on cancer patients identifies five types of control: processual (participation in decisions), contingency (connection between actions and outcomes), cognitive (reframing threats), behavioral (actions that alter outcomes), and existential (finding meaning that lessens threat).

Notice what's missing: actual control over cancer cells.

My first swing—telling people, asking for help—was processual control. My second swing—understanding reports, asking questions, seeking second opinions—was cognitive and behavioral control. My third swing—naming my port Voldeport, requesting letters, creating happiness tripwires—was existential control.

Each found agency in spaces cancer couldn't touch.

Why Perceived Control Reduces Stress

In a longitudinal study of 101 breast cancer patients over one year, perceived control increased linearly while psychological distress decreased linearly. The evolution of distress could be predicted from changes in perceived control—independent of physical state changes.

Your body could be deteriorating. If your brain believed you had control, psychological distress decreased anyway.

Another study found higher perceived control associated with better quality of life in breast cancer patients, with emotional strain having the most substantial impact (44.8%).

This isn't positive thinking. It's your brain's threat assessment system recalibrating based on whether you're passive victim or active agent.

The Stress Response You Can Change

Perceived control is the perception that one has ability, resources, or opportunities to achieve positive outcomes through one's own actions.

Notice: perception of ability. Not actual guarantees.

When I couldn't prevent cancer, I asserted control elsewhere:

Choosing who drove me to chemo (behavioral)

Understanding every treatment option (cognitive)

Creating joy rituals cancer couldn't touch (existential)

Psychological interventions that enhance cognitive coping and perceived control reduce cortisol responses to stress. Your HPA axis—your body's stress system—responds to your perception, not just the stressor.

When friends triangulated oncologist recommendations, they weren't curing cancer. They gave my brain evidence I had resources. That perception reduced my physiological stress response.

What This Means for Your Next Curveball

Perceived control protects against stress's detrimental effects on persistence. Stress impaired persistence when setbacks were uncontrollable, but not when perceived as controllable.

Not actual control. Perceived control.

That email asking for help wasn't controlling cancer. It was controlling who knew, what I asked for, how I engaged my community. Small choices signaling to my brain: you're not helpless.

The letters weren't chemotherapy. But they proved I could still receive love, connect with my kid, create joy during treatment. My brain registered agency.

Naming my port didn't shrink tumors. But it reminded me and every nurse: I'm still the person who makes choices here.

The Prescription Your Oncologist Can't Write

Research consistently shows that problem-focused engagement coping and perceived control interact to predict lower anxiety and depression symptoms in cancer patients. But perceived control alone—without that active engagement—doesn't do much.

You need both. The belief that you can influence outcomes AND the actions that reinforce that belief.

Which is why the three swings matter:

First swing (Connection): You tell people. You ask for specific help. You create evidence that you have resources and aren't facing this alone. Your brain registers: not helpless.

Second swing (Self-Advocacy): You understand your pathology. You ask questions. You get second opinions. Your brain registers: I'm actively participating in my care decisions.

Third swing (Joy): You create happiness tripwires. You name medical devices ridiculous names. You schedule moments of delight. Your brain registers: cancer doesn't control everything.

None of these gives you control over cancer itself. But they give your brain evidence of control over something. And your brain's threat response system recalibrates accordingly.

The Question That Changes Everything

You're standing at the plate. The curveball is coming. You didn't choose this pitch.

But here's what neuroscience confirms: your brain is waiting to see what you do next. Not because your actions will necessarily change the outcome. Because your actions will change how your brain interprets the threat.

You don't need to control cancer. You need to show your brain that you're not powerless in its presence.

Where's your control today? Not over cancer cells. Over your response. Your choices. Your connections. Your joy.

Your brain is listening.

Reflection Questions:

Which type of control (processual, cognitive, behavioral, existential) feels most accessible to you right now?

What's one small action you can take today that would signal to your brain: I have agency here?

Where have you been trying to control outcomes instead of controlling your response to outcomes?

Who in your life could help you create evidence of resources and support (like my friends triangulating oncologist referrals)?

What's your version of "Voldeport"—a small act of rebellion that reminds you cancer doesn't control everything?