Stop Being So Damn Tired

The Precision Strategy That Kills Post-Cancer Fatigue

The exhaustion won’t quit. Your chemo’s done. Surgery’s behind you. But you’re still so tired you can barely climb your own stairs.

Your oncologist shrugs. “That’s normal,” they say. Maybe they mention getting more rest. Eating well. Taking it easy.

Meanwhile, you’re wondering if this exhausted version of yourself is permanent.

Let’s talk about why you’re still exhausted six months after treatment ended. Not in vague “be patient with yourself” terms, but in actual metabolic science that explains what’s happening in your body.

Watch/listen to Dr. Amy Morris on the Kicking Cancer’s Ass podcast.

When Dr. Amy Morris—former cancer pharmacist turned ovarian cancer survivor—started researching treatment-induced fatigue, she discovered something that changed her approach to recovery: cancer fundamentally rewires your metabolism, and most of us are feeding that altered metabolism exactly the wrong way.

Your Body Isn’t Working Like It Used To

Here’s what happens during treatment that nobody explains clearly: your body enters a state researchers call “cancer cachexia”—a metabolic disorder characterized by tissue wasting that persists even when you’re eating enough calories.

Cancer cells force your body to rely heavily on glucose as its main fuel source, mobilizing glucose from muscle and fat tissue. Meanwhile, systemic inflammation disrupts how muscle and fat cells make and use energy. This affects up to 80% of people with advanced cancer, and its effects linger long after treatment.

“When you’re sick, you know your mama, she gave you crackers or toast, right?” Amy explained. “These are the things you have when you’re sick. And so as adults we think, okay, I just want to eat gentle carbs.”

That instinct makes sense. It’s comforting. It feels safe.

It’s also exactly wrong for metabolic recovery.

The Protein Problem Nobody’s Solving

Most oncologists tell patients to “eat well” and “maintain good nutrition.” What they rarely explain is that your protein needs during and after treatment are radically different from normal.

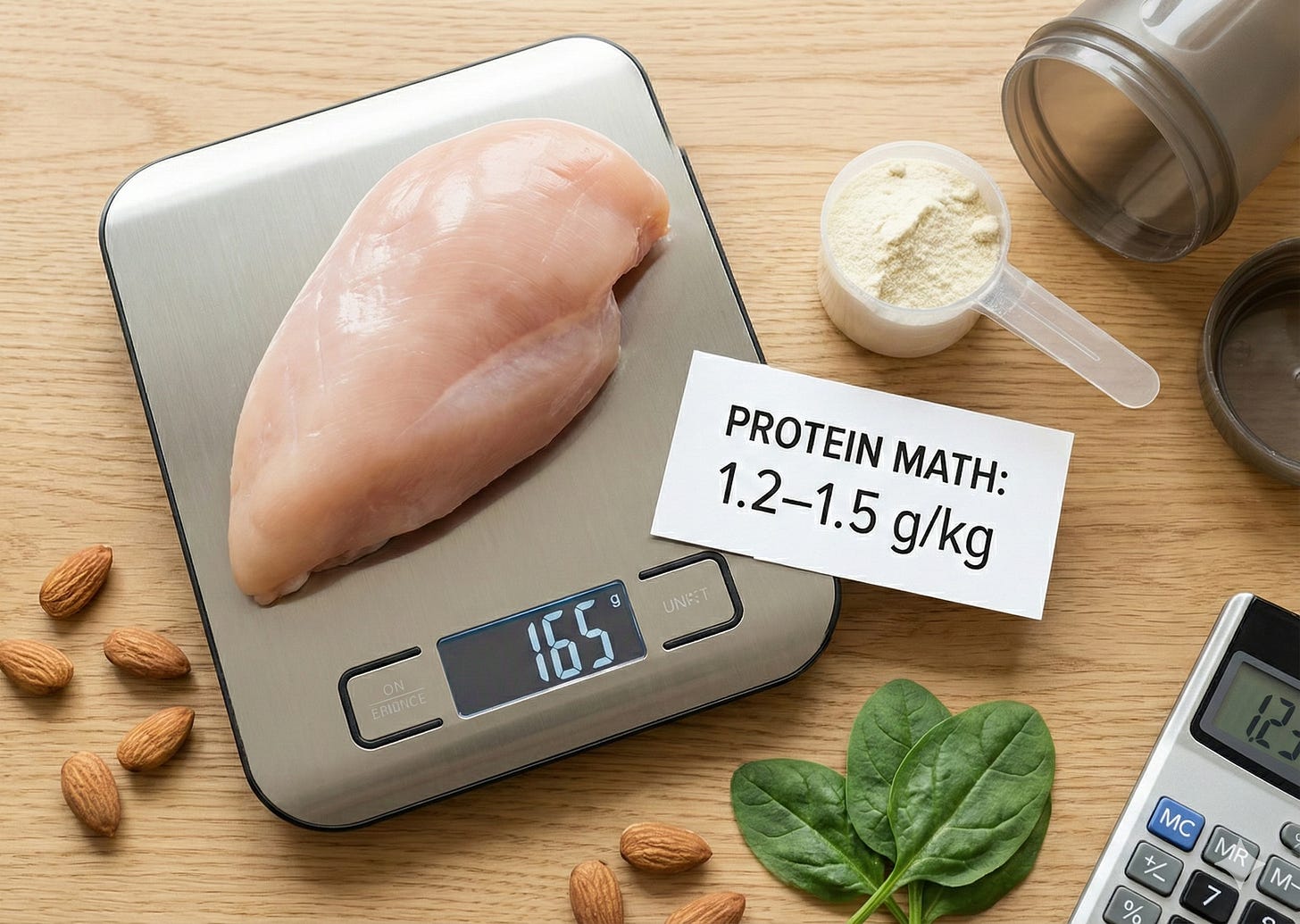

Current guidelines suggest 1.2–1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily for cancer patients, compared to 0.8 g/kg for healthy adults. Many cancer patients don’t meet these levels, often due to treatment side effects.

Here’s what that means: if you weigh 150 pounds (about 68 kg), you need 82–102 grams of protein daily. That’s roughly a chicken breast at breakfast, lunch, and dinner—every single day.

“How much of your food goes to protein, how much to carbohydrates, how much to fat?” Amy asked. “And then we look at micronutrients to make sure we’re achieving the right levels to really fine tune that energy and get it back.”

This precision matters because adequate protein maintains and rebuilds lean body mass, with research showing significant improvement in energy intake and reduced complications with proper supplementation.

The Micronutrient Crisis Nobody’s Checking

While protein gets some attention, micronutrient deficiencies fly under the radar—despite their massive impact on fatigue and recovery.

Take vitamin D. Studies report 85–92% of breast cancer patients are vitamin D deficient. Nearly nine out of ten. This deficiency impairs immune function, increases complications, and contributes to fatigue and depression.

Vitamin D deficiency before treatment increases the likelihood of bacterial infection during treatment. Your body is trying to heal while fighting infections it shouldn’t have—all because nobody checked your vitamin D levels.

Cancer- and treatment-induced micronutrient deficiency impacts disease course and treatment effectiveness, increasing complications such as impaired immunity, delayed wound healing, fatigue, and depression.

“Lots of women will say, I eat whole foods, I eat organic, I eat mostly clean,” Amy explained. “All of these things that are typically very healthy, but healthy during and after chemo’s got to look a lot different than healthy for just the regular person.”

Why “Healthy Eating” Isn’t Enough

The disconnect between what we think of as healthy eating and what recovery requires comes down to specificity. Eating organic vegetables and lean proteins is great—for maintenance. For someone whose metabolism has been altered by treatment, it’s insufficient.

The gap between energy expenditure and intake creates a complex metabolic challenge, where addressing food intake alone doesn’t mitigate excess catabolism.

This is why Amy uses precise macronutrient targets with clients, tracking not just what they eat but whether they hit specific protein, carbohydrate, and fat ratios designed to support recovery. She measures micronutrient levels and supplements strategically based on actual deficiencies, not guesswork.

“This isn’t just like healthy eating,” she emphasized. “This is war and this is strategy.”

The Three Guidelines Nobody’s Following

Amy mentioned three major multinational guidelines for cancer nutrition—professional groups that reviewed the best evidence and created recommendations. What do they say?

They all agree on eating “plant forward”—which Amy distinguishes from vegetarian.

“Eating plant forward means the presence of plants,” she explained. “Vegetarian means the absence of meat. One is restriction, one is strategy.”

The difference matters enormously. In the cancer space, where many people already feel deprived by treatment, adding restrictions rarely helps. What helps is strategic addition: more protein, more plants, more targeted micronutrients.

“You probably already restricted enough,” Amy noted. “So now let’s focus on the strategy.”

The Exercise Component: Your 59% Advantage

Beyond nutrition, Amy shared research showing that exercise reduces the risk of recurrence by 59%. Not gentle walks (though those help). Target levels: 150 minutes of low-to-moderate cardio weekly, plus 20–30 minutes of full-body strength training 2–3 times weekly.

“So 150 minutes per week works out to 21 minutes a day,” she calculated. “We spend 20 minutes scrolling our phones doing nothing. We have a rule in our house. You can scroll your phone as long as you want, but you get on the walking pad and do it.”

Only 4% of cancer survivors hit these target levels. The 59% risk reduction comes from a systematic review analyzing tens of thousands of cancer survivors—arguably the highest level of evidence.

What This Means for You

If you’re exhausted months after treatment, your oncologist might say this is your “new normal.” Amy’s response?

“There is no new normal. You don’t have to get used to a new normal. You can be the healthiest version of you ever.”

But getting there requires understanding that your body’s metabolic needs have changed, probably in ways you haven’t addressed. It requires precision in protein intake, attention to micronutrient status, and a willingness to think about food as fuel for specific metabolic processes.

The exhaustion isn’t punishment. It’s not permanent. It’s not your fate.

It’s a solvable metabolic puzzle—if you have the right information.

Listen to the full episode:

Scientific Sources & Further Reading

The recommendations discussed in this article are based on established guidelines and systematic reviews in oncology and nutritional science.

Protein Requirements: The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) and other guidelines recommend elevated protein intake for cancer patients to support tissue repair and prevent muscle wasting.

Source: Cederholm, T. et al. (2019). ESPEN guidelines on clinical nutrition in cancer. Clinical Nutrition, 38(1), 173–200. (Recommends protein intake of 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day for cancer patients).

Vitamin D Deficiency: Multiple studies highlight the high prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies in cancer survivors, particularly Vitamin D, which is critical for immune function.

Source: Nogues, X., et al. (2013). Prevalence of serum vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in cancer: Review of the epidemiological literature. Anticancer Research, 33(5), 2217–2228. (Reports a prevalence of 85–92% Vitamin D deficiency in some breast cancer patient populations).

Cancer Cachexia: The core challenge of post-treatment fatigue is often rooted in lingering metabolic dysfunction like cachexia.

Source: Fearon, K. C., et al. (2011). Cancer cachexia: diagnosis and characterization according to the consensus definition. Clinical Nutrition, 30(5), 555-560. (Defines cachexia as a wasting syndrome that is difficult to reverse with conventional nutrition alone).

Exercise and Recurrence: The powerful impact of physical activity is supported by systematic reviews combining data across various cancer types.

Source: Kolden, G. G., et al. (2008). Exercise and cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 17(10), 1011–1025. (Systematic reviews consistently demonstrate that exercise is the most effective intervention for cancer-related fatigue, and meta-analyses support significant risk reduction figures for recurrence and mortality).

Plant-Forward Eating: Major cancer organizations advocate for a “plant-forward” approach, which focuses on inclusion rather than restriction.

Source: American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR). AICR’s New American Plate. (Recommends a diet where 2/3 or more of your plate is plant-based and 1/3 or less is animal protein, defining a “plant-forward” strategy).