Self-Trust, Not Self-Confidence: What Your Body Already Proved and Why It Changes Everything

The advice you’ve heard your whole career doesn’t work after cancer. Here’s what does — and the science backs it up.

You’ve been told your whole professional life that confidence is the thing standing between you and the next level. Speak up more. Project authority. Lean in. Just be more confident.

And maybe that advice worked, or at least felt useful, before cancer entered the picture.

But after treatment? After surgery, after radiation, after the fog lifts, and you’re sitting in a meeting, wondering why you can’t remember what you’re supposed to say next? “Just be more confident” lands differently. It lands like one more thing you’re failing at

Patricia Muir spent three decades building her consulting business. She was at the peak when breast cancer hit in 2013. Caught it early. Powered through surgery and a short course of radiation. Returned to work physically ready. And then sat alone in a boardroom and thought, “I don’t even know what I’m doing here.”

Her relationship with herself had changed, and nobody — not her oncologist, not her surgeon, not her support network — had warned her that would happen.

She’s far from alone. Research published in Supportive Care in Cancer found that across 25 studies, every single one reported reduced work engagement and work ability in cancer survivors after returning to the job. It is a diminished sense of self while doing the work. That gap between medical clearance and functional performance is real, and it has almost nothing to do with whether your body is physically ready.

The Confidence Trap

Patricia is an executive coach who specializes in emotional intelligence. She didn’t talk about rebuilding confidence. She talked about building self-trust.

“Women, going through a long career, we’re told all we need is a little more confidence,” she told me. “So that’s telling us we’ll never be there, because we’ll always need more.”

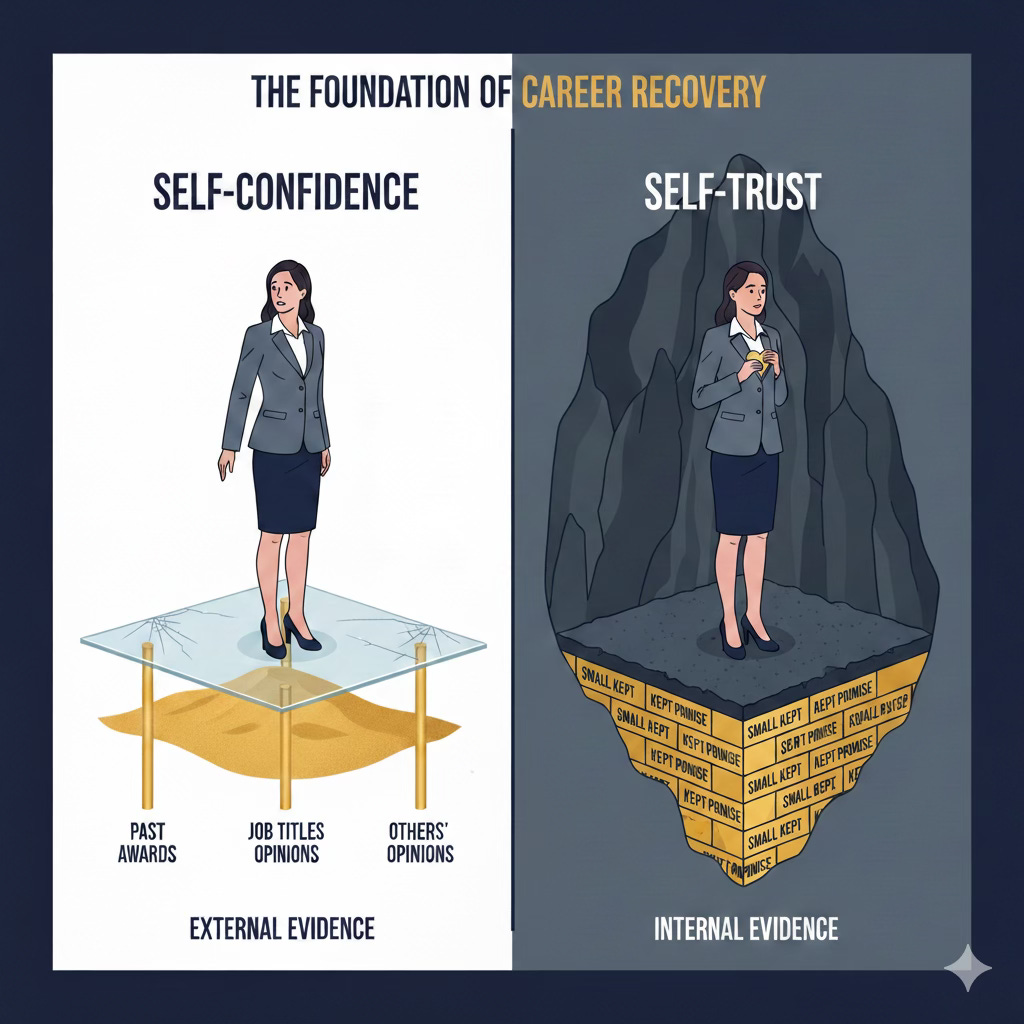

I love a good reframe. Confidence is external validation turned inward. It’s the belief that you can do something because you’ve done it before, because people tell you you’re good at it, because your track record says so. But cancer disrupts the track record. Your body changed. Your energy changed. Your emotional landscape shifted. The evidence that fueled your confidence doesn’t quite match who you are now.

What Patricia calls “self-trust” has a close cousin in the research world. Psychologist Albert Bandura called it self-efficacy: your belief in your ability to execute a specific task. The difference between self-efficacy and general confidence matters enormously. Confidence is a feeling. Self-efficacy is evidence-based. Bandura identified four ways people build it, and the most powerful one is what he called “mastery experiences” — successfully completing a task and using that success as proof you can do it again.

That’s what Patricia prescribes. Make a small promise to yourself. Keep it. Make another one. Keep that too. Each kept promise is a mastery experience without waiting for confidence to arrive. Generate evidence that you can trust yourself, one commitment at a time.

Research in oncology specifically supports this approach. A study published in PMC on breast cancer survivor self-efficacy found that without intervention, self-efficacy and adjustment tend to decrease over time after treatment. But targeted self-efficacy interventions — the kind that build from small, achievable actions — improve quality of life, reduce symptom distress, and increase self-care behaviors. Patricia’s framework is backed by decades of clinical data.

Your Body as Proof, Not Problem

Patricia doesn’t frame your post-cancer body as something you have to overcome. She frames it as evidence.

“Think about how magical that body is,” she said. “That body has been able to go through this kind of treatment. Recognize that. Celebrate that.”

This reframe has structural consequences for how you approach your career after treatment.

If you believe your body failed you — that it’s the thing that derailed your career and your life — then every professional decision you make is colored by distrust. Distrust of your energy. Distrust of your stamina. Distrust of whether you can handle the next client, the next quarter, the next crisis.

But if you start from the position that your body just accomplished something difficult and extraordinary, you’re building on a foundation of evidence.

Researchers Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun have spent decades studying what they call post-traumatic growth — positive psychological changes that emerge not in spite of trauma but through the struggle to process it. Their research found that cancer survivors consistently report growth in five specific areas: greater personal strength, new possibilities, deeper relationships, increased appreciation for life, and spiritual development. A 2023 scoping review of 109 studies confirmed that these findings hold across cancer types and cultures, and that growth stems specifically from the cognitive work of rebuilding your sense of self after the old framework is shattered.

Here’s the paradox Tedeschi and Calhoun identified that I think every cancer survivor recognizes: “I am more vulnerable, yet stronger.” Both things are true at the same time. Your body has changed. And it proved something remarkable.

I think about this through kintsugi — the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold. The repair doesn’t hide the break. It makes the break part of the object’s beauty and history. Your scars, your fatigue, your changed relationship with time and energy — those aren’t weaknesses to conceal in the boardroom. They’re the gold lines of someone who came through something and emerged different, beautiful, and strong.

The Three Paths (And How to Know Which One You’re On)

Patricia maps three trajectories from the moment of diagnosis. The first leads through reflection toward what she calls a new level of peak performance — not a return to the old peak, but a different one, shaped by who you are now. The second path runs through questioning into passive performance — you’re at your desk, you’re doing the work, but you’ve checked out emotionally. The third spirals from disillusionment to disengagement and eventually to leaving, not on your terms.

Which path you land on has less to do with your prognosis and more to do with whether you can build self-trust in the months after treatment ends.

Patricia’s program takes a full year using the Bar-On model, which maps competencies across self-perception, stress management, decision-making, and interpersonal skills. The Bar-On model identifies self-regard as the foundational component: your ability to respect and accept yourself as you are. Cancer takes a hard toll on self-regard, and Patricia’s experience coaching executive women confirms what the model predicts: if you don’t rebuild that foundation, everything else wobbles.

“You cannot fix your emotional state in one coaching session,” she told me. No, you can’t. And you can’t fix it by pretending treatment was just a bump in the road, either.

What You Can Do This Week

Make one promise to yourself. Something small, something only you will know about. Keep it. Then make another one tomorrow. Collect evidence that you can trust yourself. Bandura would call these mastery experiences. Patricia would call them self-trust. I call them proof of your power and resilience.

Stop chasing the pre-cancer version of your performance. That woman faced different challenges. You faced cancer. The measurement has changed because you have changed.

And if someone tells you it’s all over now and you should get back to normal? Know this: it’s never all over for a cancer patient. Normal doesn’t exist anymore. But what does exist — what Patricia found 12 years after her diagnosis — is something better. She redesigned her business to work only with the clients who bring her joy. She chose purpose over adrenaline.

You never choose the pitch. But you always choose the swing.

👉 Tune in to the full episode: YouTube | Spotify | Apple | Everywhere

Links and More Information

Learn more about Patricia’s coaching - https://www.patriciamuir.com/

Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory (overview): https://www.simplypsychology.org/self-efficacy.html

Bandura’s Theory of Self-Efficacy: Applications to Oncology (Lev, 1997): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9188268/

Breast Cancer Survivor Self-Efficacy Scale (BCSES) — PMC: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4869969/

Tedeschi & Calhoun — Post-Traumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence (2004): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247504165_Tedeschi_RG_Calhoun_LGPosttraumatic_growth_conceptual_foundations_and_empirical_evidence_Psychol_Inq_151_1-18

Post-Traumatic Growth in Adult Cancer Survivors: Scoping Review of 109 studies (2023): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12392248/

Return to Work Among Breast Cancer Survivors: A Literature Review (Sun, Shigaki & Armer, 2017): https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00520-016-3446-1

Bar-On Model of Emotional-Social Intelligence (2006): https://www.eiconsortium.org/reprints/bar-on_model_of_emotional-social_intelligence.htm

Emotional Intelligence and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review (2024): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10838802/